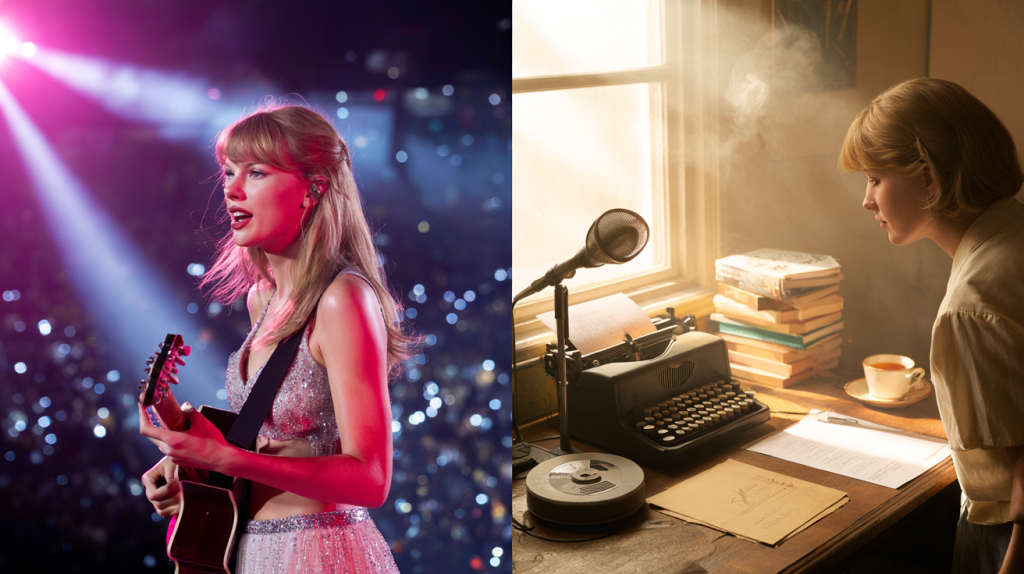

Two names keep colliding in timelines and group chats: Taylor Swift and Sylvia Plath. One shapes the sound of stadiums, the other reshaped confessional poetry. The link is not a meme. It starts with the same high-wire act, the intimate voice delivered at mass scale, the diaristic I that sounds like a heartbeat pressed to a mic.

The comparison surged again with Taylor Swift’s 2024 album “The Tortured Poets Department”, released on 19 April. At the same time, numbers underline the cultural stakes. Pollstar reported The Eras Tour grossed about 1.04 billion dollars in 2023 on 4.35 million tickets, while the concert film crossed roughly 261 million dollars worldwide according to AMC Theatres. Sylvia Plath’s legacy sits differently, yet firmly: “The Collected Poems” earned a Pulitzer Prize in 1982, “Ariel” was published in 1965 after her death in 1963, and “The Bell Jar” first appeared in 1963 in the United Kingdom. Same magnetism, different mediums, similar pull on readers and listeners.

Why the Taylor Swift and Sylvia Plath comparison will not fade

The immediate spark is linguistic and thematic. Sylvia Plath’s late poems, many written in 1962, turned private anguish and fiercely controlled metaphor into public literature. Taylor Swift’s songwriting rides a comparable intimacy, where private dilemmas move through crisp images and recurring motifs, then land in millions of earbuds the same week.

Scale changes the effect but not the mechanic. Taylor Swift now holds 14 Grammy Awards after the 2024 ceremony, including a record fourth Album of the Year, as recognized by the Recording Academy in February 2024. Sylvia Plath published a single novel and a small, stunning body of poems, yet sits on school and university syllabi across decades. Both turn self into lens, then the lens into a lighthouse.

There is also the album itself. “The Tortured Poets Department” explicitly nods to a literary frame, and even includes a printed poem from Stevie Nicks in the physical edition, a detail noted across music press in April 2024. Listeners heard a bridge between diaristic pop and confessional poetry, then went hunting for the map.

Craft first: confession, control and how the language works

Start with technique, not myth. Sylvia Plath’s voice leans on stark metaphor, sonic patterning, and a theatrical control of address. In “Lady Lazarus” she closes with “I eat men like air”, the shock line landing after layered rhythms and staged resurrections. It reads intimate, but the scaffolding is formal and exact.

Taylor Swift’s best writing often mixes diaristic detail with structural payoffs. A throwaway object returns in the chorus, a scene flips meaning by verse three, a bridge slides into new key colors. The confessional feel is deliberate craft, not a journal page torn out at random. That is the shared neighborhood: the blunt candor, then the surprise precision.

One more overlap, the curated self. Plath recorded for the BBC in 1962, reading and framing her own work in a controlled radio context. Taylor Swift designs narrative arcs across album eras and re-recordings, a long game that turns private material into staged chapters. Both show authorship as performance and archive.

Impact by the numbers: audiences, awards and endurance

Evidence matters when claims get loud. Taylor Swift’s measurable reach is vast. Pollstar’s 2023 year end report placed The Eras Tour above one billion dollars in gross, the first tour to cross that line in a single year of reporting. The Recording Academy’s February 2024 wins confirmed a rare pattern of critical and commercial alignment.

Sylvia Plath’s numbers are different, historical and institutional. “Ariel” appeared in 1965 in the United Kingdom and in 1966 in the United States. “The Bell Jar” reached American readers in 1971. The Pulitzer Prize for “The Collected Poems” arrived in 1982, nearly two decades after her death. The endurance shows in continuous new editions and in persistent classroom presence. Less weekend box office, more long tail canon formation.

So the comparison holds along two axes: similar confessional engines, divergent distribution systems. One routes through streaming platforms and sold out venues, the other through syllabi, archives and prizes. Different highways, related destination.

How to read the comparison without flattening either artist

The trick is not to confuse confession with spontaneity. Both artists build intimacy through design. Treat that design as the story.

Context also matters. Sylvia Plath wrote within a mid century confessional movement that included Robert Lowell and Anne Sexton, with specific postwar pressures and gendered expectations. Taylor Swift writes inside a digital attention economy, where reception loops back into creation within hours. Same candor, different audience physics.

For a practical path, pair texts and tracks, then check the time stamps and the venues where they first lived. Short sessions work best when the comparison feels noisy online.

- Read “Ariel” in the 1965 arrangement, then the 2004 restored edition, to see how sequence alters meaning, and listen to Taylor Swift’s 2024 album straight through to notice narrative order.

- Match a Plath poem recorded for the BBC in 1962 with a live Taylor Swift performance from The Eras Tour, noticing how voice and setting shift reception.

- Place awards beside dates: Plath’s 1982 Pulitzer and Swift’s 14 Grammys as of 2024 outline two very different validation systems.

- Keep an eye on publication frames: “The Bell Jar” 1963 release in the United Kingdom under Victoria Lucas, then later in the United States, alongside Swift’s re recorded albums that revisit ownership and context.

Read closely, then step back. The point is not to declare a winner. It is to understand why a lyric built for a stadium and a poem written in 1962 can feel like they are whispering from the same seat. The comparison is definitly loud right now, but the reasons rest in craft, timing, and the way audiences meet confession across decades.